Industrial ethanol is one of the most versatile and essential chemicals in the modern world. You’ll find it in everything from solvents and cosmetics to pharmaceuticals and industrial-grade cleaners. Yet, for such a critical ingredient, its production process is widely misunderstood, often confused with that of food-grade spirits or fuel.

As a specialist manufacturer with 20 years of experience producing high-purity ethanol, we believe in transparency. The real expertise isn’t just in making ethanol; it’s in producing the right grade for the right application with unwavering consistency.

This guide will walk you through the complete industrial ethanol production process, from raw feedstock to the final, specialized product. We’ll cover the science, the steps, and the critical quality measures that separate a bulk commodity from a high-stakes industrial solution.

What Is Industrial Ethanol, Really?

Before we dive into the “how,” let’s clarify the “what.” The primary difference between industrial ethanol and the ethanol in alcoholic beverages has almost nothing to do with the initial production—it’s all about the final step and the intended use.

Industrial ethanol is simply ethanol (C2H5OH) designated for non-consumptive applications. It is chemically identical to food-grade ethanol but is handled, taxed, and sold differently.

How does “industrial” differ from “food” or “fuel” grade?

The key differentiator is a single word: denatured.

To avoid the extremely high taxes on consumable spirits, industrial ethanol is made unfit for human consumption by adding specific additives called “denaturants”. This is the most critical step for industrial applications and a specialty we’ve perfected at Le Gia.

Here’s a simple breakdown:

| Grade | Primary Purity | Key Differentiator | Common Use |

| Food-Grade | ~95% (190 Proof) | Regulated for human consumption; no additives. | Alcoholic beverages, food flavorings. |

| Fuel-Grade | ~99.5%+ | Denatured (usually with gasoline) to be used as a fuel additive (e.g., E10). | Biofuel, blended with gasoline. |

| Industrial-Grade | 95% – 99.9% | Denatured with specific agents (like methanol or isopropanol) to be tax-exempt and unfit to drink. | Solvents, cleaning, cosmetics, inks. |

What are the primary industrial applications?

Industrial ethanol’s power lies in its versatility as a solvent. It can dissolve oils, resins, and other compounds that water cannot, but it’s also less toxic than harsher solvents like methanol.

As a manufacturer supplying industries worldwide, we see it used everywhere:

- Solvents: In the production of paints, inks (for clients like Siegwerk), lacquers, and coatings.

- Cleaning & Disinfection: For cleaning electronics, medical devices, and as a base for industrial-strength sanitizers.

- Cosmetics & Pharma: As a carrier in perfumes, lotions, and some pharmaceuticals.

- Chemical Synthesis: As a “feedstock” itself, used as a building block to create other chemicals.

Which Raw Materials (Feedstocks) Are Used?

Industrial ethanol can be made from two primary sources: biological fermentation or synthetic (petrochemical) processes. At Le Gia, we specialize in naturally-sourced, fermented ethanol, which begins with a plant-based feedstock.

The choice of feedstock depends entirely on regional agriculture, cost, and availability.

Why is corn the dominant US feedstock?

In the United States, corn is king. The vast majority of US-produced ethanol is for the fuel industry, and corn is the most abundant, cost-effective, and government-subsidized starch source available. The production method used is typically dry milling or wet milling, which involves grinding the entire kernel or separating its parts first.

How is the molasses-based process different?

Outside the US, particularly in Asia and sugar-producing nations, molasses is a preferred feedstock. Molasses is a thick, dark syrup that is a byproduct of sugar refining. Le Gia is not only a producer of ethanol but also a supplier of molasses, so we manage this supply chain directly.

The advantage of molasses is that it already contains simple sugars. Unlike corn, which is a starch and must be broken down, molasses can be fed directly to the yeast, simplifying the first steps of production. This makes it a highly efficient and cost-effective raw material.

What about synthetic (petrochemical) production?

Industrial ethanol can also be produced synthetically by the hydration of ethylene, which is derived from petroleum or natural gas. This process creates a very high-purity product, but it is a fossil-fuel-based chemical. As market demands shift toward sustainability and renewable sourcing, bio-ethanol from fermentation (like corn or molasses) has become the focus for many, including us.

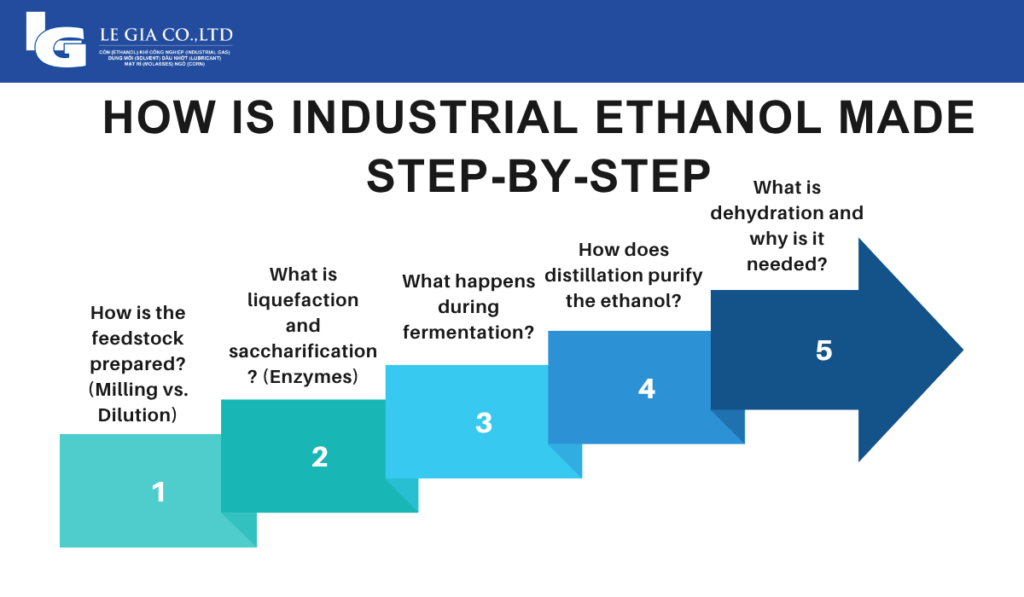

How Is Industrial Ethanol Made Step-by-Step?

Regardless of the feedstock, the biological process follows five core steps. We’ll cover the process for both starch (corn) and sugar (molasses).

Step 1: How is the feedstock prepared? (Milling vs. Dilution)

First, the sugar must be made accessible to the yeast.

- For Starch (Corn): The corn kernels are ground into a fine powder called “meal”. This is the “dry milling” process. This meal is then mixed with water to create a “mash.”

- For Sugar (Molasses): This step is much simpler. The thick molasses is simply diluted with water to create a “wash” with the perfect sugar concentration for the yeast.

Step 2: What is liquefaction and saccharification? (Enzymes)

This step is critical for starch feedstocks like corn but is skipped for molasses.

A starch is just a long chain of sugar molecules. Yeast can’t eat it directly. The “mash” must first be broken down.

- Liquefaction: The corn mash is heated and enzymes (like alpha-amylase) are added to break the long starch chains into smaller, more manageable chains.

- Saccharification: The mixture is cooled, and a second enzyme (glucoamylase) is added to break those smaller chains into simple sugars (glucose) that yeast can ferment.

Step 3: What happens during fermentation? (The role of yeast)

This is the biological heart of the process. The sugar-rich mash (from corn) or wash (from molasses) is pumped into large fermentation tanks, and yeast (typically Saccharomyces cerevisiae) is added.

The yeast is a living microorganism that consumes the sugar in an anaerobic environment (without oxygen). In doing so, it produces two things: ethanol and carbon dioxide (CO2). This process takes 24-72 hours, resulting in a “beer” or “wash” that is about 10-15% ethanol by volume.

Step 4: How does distillation purify the ethanol? (To 95%)

Now, we must separate the 10-15% ethanol from the water and solid byproducts. This is done through distillation, which uses the different boiling points of ethanol (78°C) and water (100°C).

The fermented “beer” is pumped into a tall distillation column. As it’s heated, the ethanol evaporates first, rising to the top of the column as a vapor. This vapor is then cooled and condensed back into a liquid. Through a series of columns, this process is repeated, achieving a maximum purity of 95-96% ethanol.

Why does it stop at 95%? This is a famous limit in chemistry. Ethanol and water form an “azeotrope,” a mixture that boils at a single temperature, making further separation by standard distillation impossible.

Step 5: What is dehydration and why is it needed? (Molecular Sieves)

For many industrial and all fuel applications, 95% purity isn’t high enough. That remaining 5% of water must be removed. This final water-removal step is called dehydration.

The most common modern method is using molecular sieves. The 95% ethanol is passed through beds of synthetic beads (zeolites) that are designed to trap water molecules while allowing the larger ethanol molecules to pass through. This “dries” the ethanol, resulting in a nearly 100% pure product (99.5%+) known as anhydrous ethanol (“anhydrous” meaning “without water”).

What Is Denaturing (And Why Is It The Most Critical Step)?

At this point, we have high-purity ethanol. It could be used for food, fuel, or industry. The next step is what defines it as industrial-grade and is, for our clients, the most important part of the process.

As a “trusted specialist in Ethanol Denaturation”, this is our expertise.

How is ethanol denatured?

Denaturing is the process of adding specific chemicals (denaturants) to the ethanol to make it poisonous, bad-tasting, or otherwise unfit for human consumption.

This is not a random process. Denaturing formulations are highly regulated and specific to the end-use. A common formulation might be adding a small percentage of methanol, isopropanol, or another bitterant. We specialize in creating these tailored and compliant solvent formulations to meet complex industrial requirements.

Why is denaturing required for industrial use?

The reason is purely economic and regulatory. Governments levy massive taxes on consumable alcohol. By denaturing the ethanol, it is re-classified as a tax-exempt industrial chemical, making it economically viable for use in paints, inks, and other products.

Using undenatured (food-grade) ethanol for an industrial process would be astronomically expensive. Therefore, a reliable, compliant denaturing process is the cornerstone of the entire industrial ethanol supply chain.

How Do Producers Ensure Quality and Purity?

If you’re a B2B buyer, the process is interesting, but the consistency is what matters. A bad batch of solvent can ruin an entire product line. This is where a manufacturer’s experience and quality systems become paramount.

After 20 years in production, we know that quality control is a continuous loop.

What quality control tests are performed?

You can’t just trust the process; you must verify the product. We maintain consistent product quality by testing at every stage.

- Feedstock: Testing incoming molasses or corn for sugar content and impurities.

- Fermentation: Monitoring temperature, pH, and sugar conversion in real-time.

- Final Product: Before a single drop is shipped, the final ethanol is tested in a lab for:

- Purity (Assay): Using gas chromatography to verify the exact percentage (e.g., 99.9%).

- Impurities: Testing for trace amounts of methanol, aldehydes, or other contaminants.

- Water Content: Ensuring it meets anhydrous specifications.

- Denaturant Level: Confirming the exact formulation for regulatory compliance.

What do certifications like ISO 9001 mean?

When you see a certification like ISO 9001:2015 or GMP (Good Manufacturing Practices) on a supplier’s profile, it’s not just a logo.

- ISO 9001:2015 means the company has a proven, documented, and audited Quality Management System. It’s an external validation that we “always deliver on commitments” and “maintain consistent product quality”.

- GMP ensures that the production process itself is robust, repeatable, and designed to prevent contamination.

These systems are your assurance that the 1,000th drum of ethanol you receive will be identical to the first.

How Does the Industrial Supply Chain Work?

The process doesn’t end when the ethanol is made. For industrial clients, getting the product where it’s needed, in the right blend, is just as important.

As a company that controls the full supply chain—from production and trading to blending and export—we manage complexities that pure traders cannot.

How are feedstocks like molasses sourced?

A stable supply of ethanol requires a stable supply of raw materials. We maintain a robust supply chain for key feedstocks like molasses. This vertical integration helps protect our clients from the price volatility and shortages that can plague the market.

What are the logistics of blending and transport?

Most industrial clients don’t just need pure ethanol; they need a specific blend. This is where our flexible blending services become a key advantage.

We can blend ethanol to a customer’s exact specifications, creating tailored solvent formulations for their unique process. Having “international export experience” means we also manage the complex logistics and documentation required to ship these products safely and compliantly to markets across Asia and the world.

How Do You Choose a Reliable Ethanol Supplier?

The industrial ethanol production process is a complex balance of agriculture, chemistry, and logistics. When choosing a partner, you’re not just buying a chemical; you’re buying their process, their quality control, and their experience.

Why does 20 years of experience matter?

With two decades of experience, a manufacturer has navigated feedstock shortages, regulatory changes, and complex client demands. This expertise ensures a “Quality and Stable Supply” and the “Industry expertise” to solve problems before they affect your business.

Why ask about flexible blending services?

Your process is unique. A supplier who can only offer a “one-size-fits-all” product will force you to compromise. A true partner, like Le Gia, has the “ability to blend ethanol to customers’ exact specifications”, saving you time and ensuring your product meets all technical requirements.

At Le Gia, we are more than a supplier; we are your expert partner in high-quality ethanol solutions.

Looking for a stable, high-purity supply of industrial, food-grade, or medical-grade ethanol? Contact our team of specialists to discuss your technical requirements and receive a competitive, transparent quote.

FAQ: Deeper Production Questions

What is an azeotrope in ethanol distillation?

An azeotrope is a mixture of two or more liquids (in this case, ethanol and water) that has a constant boiling point and composition throughout distillation. At 95.6% ethanol and 4.4% water, the mixture boils as if it were a single, pure substance, which is why standard distillation cannot be used to achieve 100% purity.

What are co-products like DDGS?

Co-products are valuable materials created during the production process. In the corn-based dry mill process, after the starch is fermented, the remaining “distillers grains” (protein, fat, and fiber) are dried and sold as a high-protein animal feed called Dried Distillers Grains with Solubles (DDGS).

Is industrial ethanol production sustainable?

It can be. The sustainability of bio-ethanol depends heavily on the feedstock and the efficiency of the production facility. Using agricultural byproducts like molasses (which Le Gia supplies) is an excellent way to create value from a waste stream. Furthermore, Le Gia is “committed… to sustainability and long-term responsibility to the community” and “actively respecting the environment”.

What is the difference between dry and wet milling?

These are the two main methods for processing corn.

- Dry Milling: The entire corn kernel is ground and fermented. This process is simpler and produces ethanol and DDGS. It’s the most common method in the US.

- Wet Milling: The kernel is first soaked to separate it into its components (starch, germ, fiber, protein). Only the starch is fermented into ethanol. This process is more complex but yields more high-value co-products like corn oil and high-fructose corn syrup.